The Faulty Logic of Equal Outcomes

Job preferences among men and women disprove a fundamental premise of inequity

Anti-racist scholar Ibram X. Kendi famously re-defined racism to mean, “a collection of racist policies that lead to racial inequity that are substantiated by racist ideas.”1 Aside from serving as a quintessential example of circular reasoning, Kendi’s definition is built on the premise that any disparate outcome between races is caused by racist policies. In his most popular work to date — How To Be An Antiracist — Kendi writes:

“Racial inequity is when two or more racial groups are not standing on approximately equal footing. Here’s an example of racial inequity: 71 percent of White families lived in owner-occupied homes in 2014, compared to 45 percent of Latinx families and 41 percent of Black families.” 2

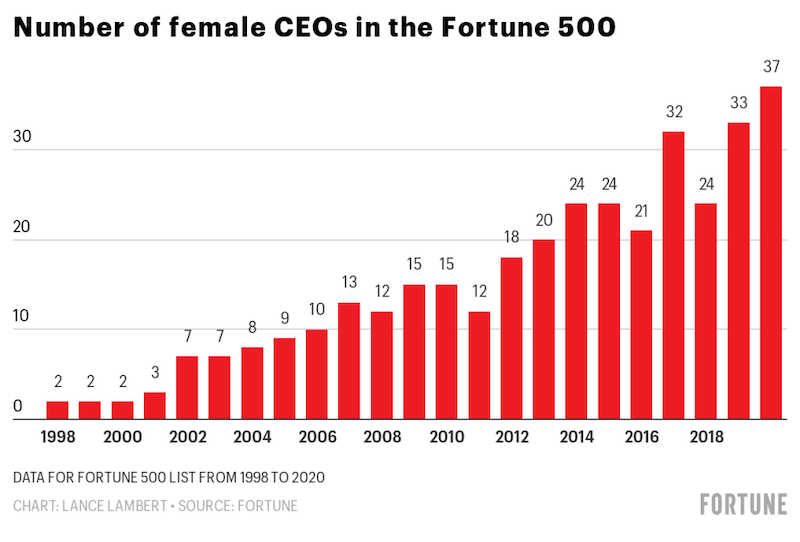

Using similar logic, pundits on gender inequity cite the paltry percentage of female CEO’s among the Fortune 500 as proof of a glass ceiling and continued discrimination against women in the United States:

The logic common to the two previous examples is the assumption that we should expect to see equal outcomes in the two metrics observed. In the first example, Kendi assumes Black and Hispanic families should have rates of home ownership similar to Whites. In the second example, experts assert we should expect to see female CEOs in numbers proportional to their representation in the US workforce — 46.8%.3 Unfortunately, these assumptions are faulty on multiple levels.

Readers of Thomas Sowell will recognize that assertions to the contrary, such observed disparities are never caused by what Sowell calls “one-factor explanations” — racist policies in the first case and sexual discrimination in the second — and more importantly that it is a logical error to expect equal outcomes. Controlling for the much higher median age of Whites (44 years) compared to Blacks (34 years) and Latinos (30 years)4, combined with the lower number of people per household for Whites and Blacks compared to Hispanics, and the relatively lower number of people in Black and Latino households earning a paycheck, the home ownership rates are much closer.5 Sowell has explained the disparate impact fallacy in multiple works, most recently in his 2018 book Discrimination and Disparities:

“What can we conclude from all these examples of highly skewed distributions of outcomes around the world? Neither in nature nor among human beings are either equal or randomly distributed outcomes automatic. On the contrary, grossly unequal distributions of outcomes are common, both in nature and among people, including in circumstances where neither genes nor discrimination are involved. What seems a more tenable conclusion is that, as economic historian David S. Landes put it, ‘The world has never been a level playing field.’ The idea that the world would be a level playing field, if it were not for either genes or discrimination, is a preconception in defiance of both logic and facts. Nothing is easier to find than sins among human beings, but to automatically make those sins the sole, or even primary, cause of different outcomes among different people is to ignore many other reasons for those disparities.”6

Sowell then proceeds to explain a range of other causal factors for disparate social and economic outcomes — geographic, demographic, cultural, temporal, differences in individual and group preferences, and random chance. As I have cited elsewhere on this blog, one of the most striking examples culled from Sowell’s decades of research on economics and culture is the revelation that Cambodian immigrants in the late 1990s owned 90% of donut stores in California even though they comprised only 0.09% of the U.S. national and 0.2% of the California populations.7 Conventional wisdom à la Kendi would explain the disparity as a conspiracy among California donut chains and retail strip mall owners to sell only to Cambodian immigrants and deprive aspiring non-Cambodians of the opportunity to earn a living selling donuts. The actual explanation, revealed by CSUN geography professors James P. Allen and Eugene Turner in their research on so-called ethnic enclaves in Southern California businesses, is that people left to their own preferences tend to choose occupations based on a combination of their unique cultural, intellectual, and environmental situation and predilections, and frequently receive advice and financial help from family or friend networks.8

The proposition that disparate outcomes prima facie prove racial and gender discrimination requires further examination. After all, Cambodian-owned donut stores in California can be a freak occurrence — an outlier in an otherwise calm sea of gender and racial balance. The fundamental assumption of the “disparate impact” theory is that one should expect to see the gender and racial makeup of business owners, boardrooms, employees, customers, and the homes they own mirror the gender and racial composition of the local or broader community. To test this hypothesis, I analyzed the most recent occupation data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS.)

It turns out the fundamental assumption of “disparate impact” theory is not just wrong, it is unequivocally wrong. Of the 385 occupations in the BLS’s Labor Force Statistics report derived from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS) that listed discernible gender breakdowns, exactly one job reflected gender harmony — Postal service mail sorters, processors, and processing machine operators. That is to say, in the 2020 CPS, roughly 148 million Americans age 16 or older were classified as “employed.” Of those individuals employed, 593 occupations were recognized using the 2018 BLS Standard Occupational Classification System. 385 of those 593 occupations listed discernible gender breakdowns (i.e. the other 208 occupations either had no data or the data did not meet publication criteria.) Of those 385 occupations with discernible gender breakdown data, only postal service mail sorters, processors, and processing machine operators reflected the workforce gender participation rate of 46.8% women and 53.2% men.9 All the other 384 occupations showed widely disparate gender breakdowns.

To show just how disparate the occupation gender breakdown is, I plotted the data below (% women is in red, % men in blue), ordered from occupations with more women than men at the top, to occupations with more men than women at the bottom:

As can be seen, there is a nearly uniform distribution of occupations from female-dominant to male-dominant. The most female-dominant occupation is preschool and kindergarten teachers at 98.8% women and 1.2% men. The most male-dominant occupation is security and fire alarm systems installers, which is 100% men with no females. If the fundamental assumption of the “disparate impact” theory was correct, one would expect most occupations to be clustered around the workforce participation mean – 46.8% women and 53.2% men. Instead, what we observe is a near linear distribution of gender differences among occupations.

Let us examine the most female- and male-dominant occupations to see if we can detect blatant examples of misogyny or misandry in the workplace. If the Kendis of the world are correct, then this should provide years worth of case leads to U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission lawyers eager to root out Title VII workforce discrimination. Here are the top 20 female-dominated occupations in the United States in 2020:

Preschools, daycare centers, medical records processors, and dental offices are not known for their blatant discrimination against male job seekers. More likely, women choose these vocations more than men do, and businesses that hire these types of workers care little about the gender of potential employees.

Here is a closer look at the top 20 male-dominated occupations:

The list is consistent with most Americans’ experience with professionals in these vocations. I have never seen nor met any female security alarm installers, brickmasons, heavy vehicle mechanics, or crane operators, nor have I ever heard complaints from females, friends or otherwise, clamoring to break into these male-dominated occupations. Instead we accept the benign explanation for why these occupations are male-dominated — men prefer these jobs more than women do.

Analyses of occupations based on race show similar disparities, though not as drastic as those based on gender. Whether viewing occupational demographics through the lens of gender or race, the norm is disparities, often vast, not concordance with the demographic breakdown of any population group.

The lack of evidence in occupation gender breakdown data to support the “disparate impact” theory does not in and of itself disprove that there is any racism or gender discrimination present in businesses or society at large, it just supports the proposition that it is highly improbable that discrimination alone accounts for observed disparate outcomes in the workplace.

Ibram X. Kendi, “How to be an Antiracist,” Random House, New York (2019), p.18.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey (2020). https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2020 estimate. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

U.S. Census Bureau, America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2016. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/families/cps-2016.html

Thomas Sowell, “Discrimination and Disparities,” 1st revised edition, Basic Books, New York (2019), p.18.

The 90% statistic was first gleaned in Thomas Sowell’s “The Quest for Cosmic Justice,” Basic Books (1999) and the census figures are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey 2000.

James Allen and Eugene Turner, “The Ethnic Quilt: Ethnic Diversity in Southern California,” The Center for Geographical Studies, Northridge, CA, 1997, pp.222-223.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey (2020.) https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm