At the La Cañada Unified School District’s (LCUSD) Governing Board regularly scheduled meeting on August 29, 2023, La Cañada High School (LCHS) Principal Jim Cartnal unveiled the launch of the pilot English 1 course modified to include Ethnic Studies. Cartnal’s announcement (see here for a video recording of his presentation) is an important milestone in the district’s multi-year effort to meet a new legal mandate from Sacramento. This will be the first time the district has incorporated critical pedagogy into a course that is required of all students.1 As I’ve pointed out previously, Ethnic Studies is often a Trojan Horse for injecting Critical Race Theory (CRT) and critical pedagogy into the regular K-12 curriculum. Whether this threshold was intentionally crossed is unclear. Previous Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) consultants hired by the district recommended the injection of CRT into LCUSD’s curriculum, and there is evidence to indicate that at least some LCUSD administrators were aware of Ethnic Studies’ pedigree in critical pedagogy and approve of its inclusion. At the same time it is also apparent that many Board members and LCHS staff remain unaware of Ethnic Studies’ lineage to critical pedagogy.

The district has previously taken a clear position renouncing the use of CRT in its standards-based instruction:

So the adoption of critical pedagogy through its pilot Ethnic Studies course violates its promise to the community. Additionally, LCUSD’s Ethnic Studies pilot program creates serious risk of inserting ideological indoctrination and undermining core education in writing and literature in its English curriculum. Parents should understand how it got here and the consequences now that critical pedagogy is inside the classroom walls.

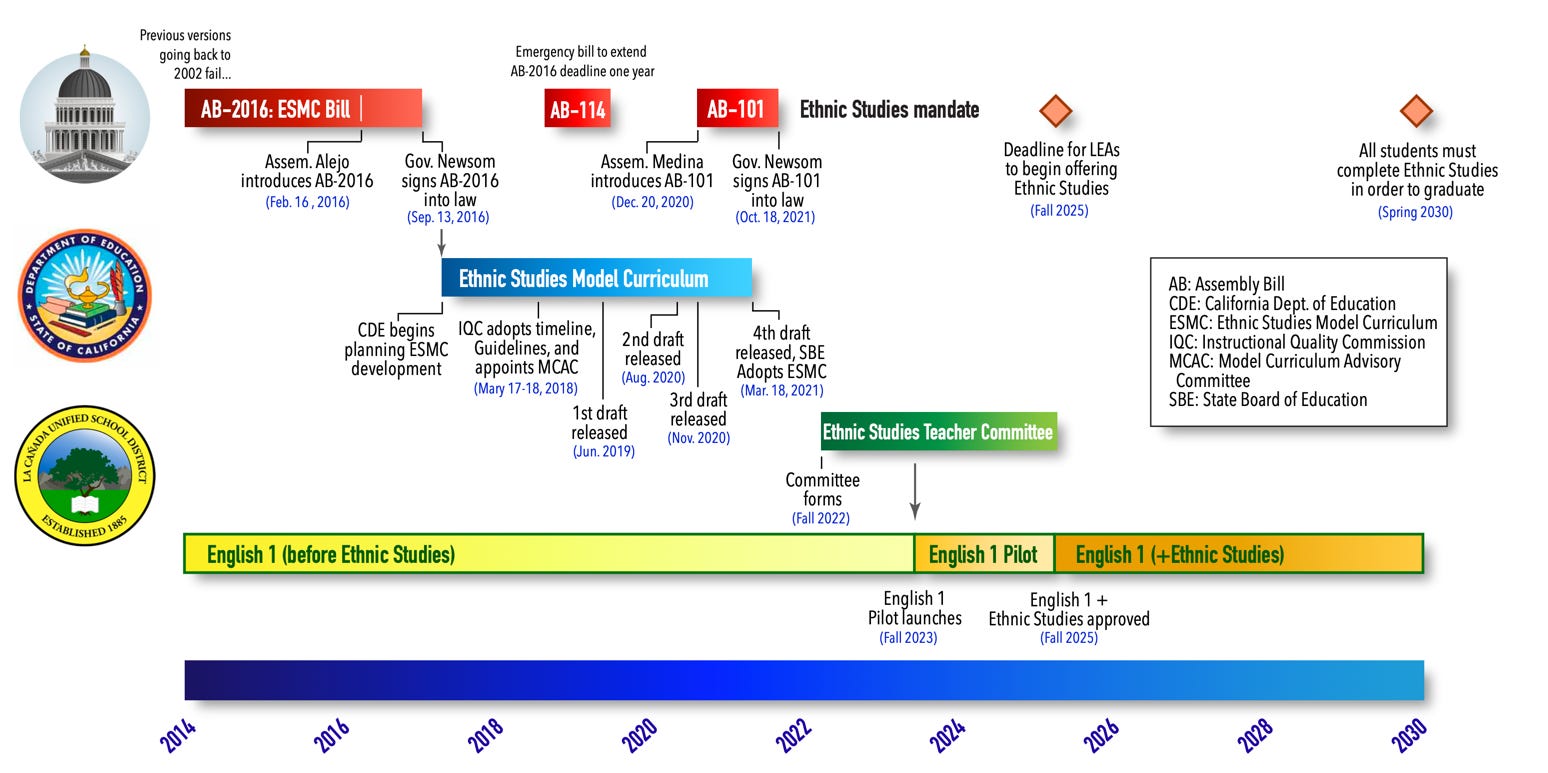

Background: The Ethnic Studies Mandate

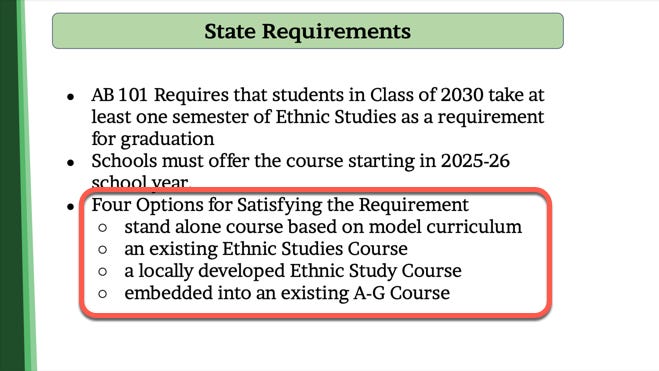

As a reminder to readers who have been following Ethnic Studies through this Substack (see previous articles here and here), the requirement to add an Ethnic Studies course as a graduation requirement was ushered in when California Governor Newsom signed into law Assembly Bill AB-101 in October 2021. AB-101 mandates that all public school students in California must complete at least one semester of Ethnic Studies as a high school graduation requirement starting with the class of 2030, though districts must start offering their Ethnic Studies courses by the 2025-26 school year.

The California Department of Education (CDE) granted wide latitude to public school districts in how to meet the Ethnic Studies requirement. As Principal Cartnal explained in his presentation to the Governing Board, districts were permitted to adopt an Ethnic Studies course based on the state’s previously developed Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (ESMC)2, they could submit an existing Ethnic Studies course already in use, they could develop their own standalone Ethnic Studies course, or they could embed Ethnic Studies into an existing UC A-G approved course such as Social Science or English language arts:3

LCUSD Associate Superintendent for Student Services Anaïs Wenn directed LCHS Principal Cartnal to convene a special committee of LCHS English department teachers to determine how to meet the AB-101 mandate in Spring of 2022. Cartnal created that Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee and they met for the first time in Fall of 2022. Surprisingly, the LCUSD Governing Board provided no constraints or requirements to Cartnal and his committee in the design of the course. The lack of oversight is surprising because it was well known at the time that the Ethnic Studies mandate and previously adopted ESMC were tremendously contentious issues that attracted widespread media attention (e.g. the Los Angeles Times published over 100 stories and editorials about the K-12 ethnic studies debate since 2018) and the district’s own hired DEI consultant Christina Hale-Elliott recommended in August 2020 that the district “include courses that highlight the experiences of historically marginalized groups (e.g., Asian studies, African American history, Chicano studies, LGBTQ studies, ethnic studies, etc.)”4

Subsequently, the subcommittee for Curriculum and Development of the district’s DEI Advisory Committee discussed Hale-Elliott’s ethnic studies recommendation at its meeting on January 28, 2021.5 In addition, I had spoken to members of the LCUSD Governing Board in 2021 to warn them of the problems in the AB-101 legislation and how critical Ethnic Studies was being implemented in schools across California.

Parents Excluded from Ethnic Studies Course Creation Process

In spite of these warnings and the vast media coverage, the Board chose not to provide oversight of Cartnal’s Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee, and it also chose not to include parents on the committee at an appropriate time as is encouraged by California Education Code and LCUSD Administrative Regulation 6161.1 (“Selection and Evaluation of Instructional Materials”):

“The district’s review process for evaluating instructional materials shall involve teachers in a substantial manner and shall encourage the participation of parents/guardians and community members in accordance with Education Code 60002.”

Of greater concern, LCHS staff and the LCUSD Governing Board misrepresented the involvement of parents in its response to the Ethnic Studies mandate. LCHS Principal Cartnal, when describing the history of the district’s response to the AB-101 mandate, told the Governing Board on August 29, 2023 that the Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee had put together a general outline and pacing guide for the modified English 1 course that includes Ethnic Studies, and they also were “continuing to review reading selections that come from a whole diverse group of students that have been through the class, from colleagues, (and) from community members.” He remarked that review of submitted reading selections had been, “a really, really rich process.” However, LCHS parents had never been told that the Ethnic Studies course creation process was underway and certainly parents had never been officially solicited for their input. A handful of parents who had been following the AB-101 debate and were aware of the Ethnic Studies course creation process through other means may have volunteered material to Cartnal over the past two years, but the courtesy was never formally extended to all LCHS parents and there is no record of who submitted what materials.

The lack of oversight of the Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee became readily apparent during its first meeting. LCHS Principal Cartnal handed out multiple documents from the ESMC to meeting attendees, with the intent of using the ESMC as a guide for determining how to meet the AB-101 requirement, even though the ESMC itself states in its Preface:

“The guidance in the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum is not binding on local educational agencies or other entities. Except for the statutes, regulations, and court decisions that are referenced herein, the document is exemplary, and compliance with it is not mandatory. (See Education Code Section 33308.5.)”

During the question and answer session after Cartnal’s presentation on August 29, 2023, LCUSD Governing Board member Dan Jeffries praised Cartnal and his committee for doing their work “in a very open and transparent way,” keeping the Board informed of what they were doing “at each step of the way,” and he said the district had gone “far beyond” the statutory requirements in allowing the opportunity for parents to hear what is going on and see proposed material for the modified English 1 course. He concluded by saying, “All those things are far beyond what was required in AB-101 and that transparency helps tremendously for our parents to understand where you are going with all of this.” This characterization is at odds with reality. Cartnal and district staff never announced the existence of the Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee to the LCHS community, never announced meeting dates to the community, never invited the community to attend any of its meetings, never recorded its meetings nor took meeting minutes, never shared any of the handouts or other materials used during its meetings (except when I made a formal request for the materials handed out at just the first meeting), nor kept the community informed of their progress except in a handful of oral reports by Cartnal and Wenn to the Board and organizations such as the DEI Oversight Committee and the LCHS Parent-Teacher-Student Association (PTSA.) Even then, those reports were perfunctory, and there was never solicitation for feedback from parents and the rest of the LCUSD community.

As I reported in November of 2022 during the last LCUSD Governing Board election, I formally asked all Board candidates to respond to the Alliance for Constructive Ethnic Studies’ (ACES) survey that was sent to all California school board candidates in September of 2022 that queried them for their thoughts on Ethnic Studies and how they planned to respond to the AB-101 mandate.6 At the time, Jeffries declined to answer ACES’ questionnaire and instead sent them the following statement:

“It is important to me that the ethnic studies course that our district approves be developed with the involvement of our community in a transparent manner and that we adopt an ethnic studies course and related professional development that is inclusive. Our ultimate goal is to promote and sustain positive school cultures where all students and staff feel welcome, safe, supported, and included on campus.”

So Jeffries’ comment to Cartnal at the August 29, 2023 Governing Board meeting seemed an attempt to convey that he had kept his campaign promise to develop an Ethnic Studies course “with the involvement of our community in a transparent manner,” when he had in fact done nothing to bring that promise to fruition. In stark contrast to his campaign statement, the district never involved the community in the Ethnic Studies course development and was not transparent by any reasonable measure. Parents’ first view of the Ethnic Studies infused pilot English 1 course was at the Governing Board meeting on August 29, 2023, two years after the process started and AFTER the course was already being taught to all LCHS 9th graders, though in a pilot mode.

What is Ethnic Studies?

The common understanding of Ethnic Studies is that it is an academic field that “examines the histories, experiences and cultures of various racial and ethnic groups and explores race and ethnicity in various social, cultural, historical, political and economic contexts.”7 It is widely regarded to be an interdisciplinary field and traces its roots to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. A coalition of race-based student groups on California college campuses— African-American, Latin-American, and Filipino-American — formed in 1968 calling itself the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) to protest what was called a “Eurocentric” curriculum and lack of diversity in college programs and courses. In response to the protests, colleges and universities across the United States created ethnic studies programs and departments, the first such being the Ethnic Studies Department at San Francisco State University in 1968.

The rise of these university programs and departments led to the proliferation of specific sub-disciplines within Ethnic Studies and the awarding of new degrees in majors, the most popular being Black American Studies (later changed by most institutions to African-American Studies), Latin-American Studies (inclusive of Mexican-American Studies, Chicano Studies, and Raza Studies), Native American Studies, and Asian-American Studies.8 The Ethnic Studies movement remained exclusively within the Academy for much of the next forty years. It did not seep into K-12 education until the 2010s.

Ethnic Studies in its plainly understood definition provides an opportunity for students to build bridges of inter-ethnic understanding, and to foster “an appreciation for the contributions of multiple cultures” as stated in the original AB-2016 bill. There are multiple ways to teach Ethnic Studies, the two most common to emerge since the AB-101 mandate being Constructive Ethnic Studies and Liberated Ethnic Studies. Constructive Ethnic Studies “focuses on educating and building understanding, while tackling challenging issues through an analytic lens. Students are taught civic responsibility, exposed to multiple political perspectives, and encouraged to develop opinions based on inquiry. Its guiding principles specifically guard against political indoctrination and are based on the History-Social Science Framework for California Public Schools.”9

Liberated Ethnic Studies, also called Critical Ethnic Studies, in contrast, assumes a critical framework, and “bring into conversation the ways that concerted efforts and collectivized resistance to US imperialism ground our approaches for dismantling the (neo)colonial schooling apparatus.”10

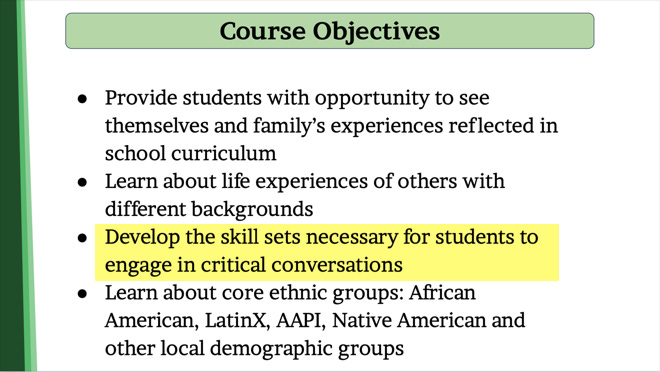

So which approach did LCUSD choose? LCHS Principal Jim Cartnal described the field of Ethnic Studies using the following slide in his Board presentation on August 29, 2023:

Note the third bullet — “(Ethnic Studies) engages with a study of identity, history and movement, systems of power, and social movements.” The inclusion of studies of systems of power and social movements is a political statement and imposes a specific theoretical viewpoint — Critical Race Theory (CRT) — whether Cartnal and his committee were aware of it or not. Cartnal described the source of this definition as coming from the CDE and its Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum. Specifically the statements in the above slide are quoted from chapter 1 (“Introduction and Overview”) of the ESMC. This is important because one must understand the origin of the ESMC to understand its Marxist roots, CRT frame of reference, and critical pedagogy orientation. Cartnal conveniently left out of his Board presentation the following CRT-framed description of what Ethnic Studies is from the same chapter, though the Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee must have certainly discussed it:

“People or person of color is a term used primarily in the United States and is meant to be inclusive among non-white groups, emphasizing common experiences of racism. The field also addresses the concept of intersectionality, which recognizes that people have different overlapping identities, for example, a transgender Latina or a Jewish African American. These intersecting identities shape individuals’ experiences of racism and bigotry. The field critically grapples with the various power structures and forms of oppression that continue to have social, emotional, cultural, economic, and political impacts. It also deals with the often-overlooked contributions to many areas of government, politics, the arts, medicine, economics, etc., made by people of color and provides examples of how collective social action can lead to a more equitable and just society in positive ways.”

Ethnic Studies as LCUSD appears to be implementing it is not then merely a study of minority racial and ethnic groups with the goal of learning about their life experiences as most would believe from the common meanings of the terms used. Ethnic Studies as presented by Cartnal and the CDE assumes a CRT approach in the examination and discussion of racism and how it affects certain marginalized minorities, and demands collective social action in response. The state did not require that districts adopt a CRT-oriented Ethnic Studies course — AB-101 left it to the Governing Board of the district to adopt whatever Ethnic Studies it wanted.11

Ethnic Studies’ Marxist Roots

As discussed previously, the academic discipline of Ethnic Studies has its roots in a Marxist student movement of the 1960s — the Third World Liberation Front. This is not the conspiratorial speculation of paranoid critics, the CDE openly acknowledges the TWLF and requires that the TWLF and its history be taught in its Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum. The CDE’s Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Guidelines, which LCHS Principal Cartnal distributed to his Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee at its first meeting in Fall 2022, explicitly states in the General Principles, the ESMC shall:

“Include information on the ethnic studies movement, specifically the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), and its significance in the establishment of ethnic studies as a discipline and work in promoting diversity and inclusion within higher education.”12

But the CDE’s insistence that the ESMC teach Ethnic Studies’ Marxist roots doesn’t stop with merely teaching about the TWLF. Also explicitly listed in the ESMC General Principles are the following Marxist tenets inherent in critical pedagogy:

“Promote self and collective empowerment

Encourage cultural understanding of how different groups have struggled and worked together, highlighting core ethnic studies concepts such as equality, justice, race, ethnicity, indigeneity, etc.

Promote critical thinking and rigorous analysis of history, systems of oppression, and the status quo in an effort to generate discussions on futurity, and imagine new possibilities.”

That ESMC’s roots are Marxist is understandable given the known political orientation of its authors. Stephanie Gregson, then Director of the Curriculum Frameworks and Instructional Resources Division for the CDE, was in charge of the development of the first draft of the ESMC, overseeing the Ethnic Studies curriculum advisory committee of the IQC and recommending 13 of its 18 members. Many of the authors of the first draft of the ESMC that Gregson selected were members of Unión del Barrio, a Marxist revolutionary organization “dedicated to struggle on behalf of La Raza living within the current borders of the United States”13 :

“We are La Raza, the people of these lands, and we challenge any and all manifestations of colonial, imperialist, and neoliberal oppression. Our use of the term La Raza is understood as meaning ‘the people’, and it encompasses the entire population of ‘Nuestra América’. It is a progressive term that unites our cultural, ethnic, gender, and racial diversity with the liberatory aspirations of indigenous and Latin American nations. Used together, La Raza de Nuestra América represents our transcontinental unity as a people, sharing a similar political conditions, cultures, histories, and class interests. The struggle of Unión del Barrio is one part of an indigenous resistance across North and South America, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, with politically imposed borders that primarily serve the interests of an international capitalist elite that is currently led by United States imperialism.”14

Unión del Barrio describes itself as is a socialist “revolutionary organization” dedicated to “self-determination and liberation,” and in their political manifesto they answer the question ‘who we are?’ with four pillars, two of which are “Ours is a National Liberation Movement Rooted in Class Struggle” and “Dialectical and Historical Materialism Form the Basis of Our Strategies and Tactics.”15

Among Unión del Barrio’s members who were co-authors or advisory committee members of the first draft of the ESMC were Jose Lara, Tolteka Cuauhtin, Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, Artnelson Concordia, Guillermo Gomez, Theresa Montano, and Lupe Cardona.16 Readers may recognize many of the names in that list as panelists on a Liberated Ethnic Studies Curriculum Consortium teacher workshop on “Demystifying CRT: Teaching Critical Race Theory in K-12 Classrooms” that I exposed in my November 2021 article on this Substack. In that teacher training workshop, Cardona admitted to teacher attendees:

“In the twenty-two years I’ve been an educator, I think students had never heard of Critical Race Theory per se until the 1,300 times it was mentioned on FoxNews -- and spread all these misinformations were spread online and what not. And so absolutely Critical Race Theory is one of the philosophical, but also very real and concrete ways I create my lessons.

…

What you will see in the lessons that follow are how classroom teachers begin to use Critical Race Theory connected to Ethnic Studies in a way to empower and to create social justice activists out of our students.”

Understandably the first draft of the ESMC released in 2019 ignited a firestorm of controversy. Ideologically left-wing, subsuming CRT throughout its pages, and characterized by critics as blatantly anti-capitalist and anti-semitic, it elicited opposition from a wide range of parent and public interest groups, as well as normally sympathetic news outlets like the Los Angeles Times and the San Francisco Chronicle.17 19,000 comments of opposition were received by the State Board of Education (SBE) during the first draft public comment period, and the opposition was so fierce that the SBE rejected the first draft. SBE President Linda Darling-Hammond said while sending the ESMC back to the IQC for a rewrite, “A model curriculum should be accurate, free of bias, appropriate for all learners in our diverse state and align with Governor Newsom’s vision of a California for all. The current draft model curriculum falls short and needs to be substantially redesigned.”18 A year later Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed an earlier version of AB-101 that would have made Ethnic Studies a graduation requirement for California’s K-12 public school students, and he apologized to Jewish citizens in California for the anti-semitism in the first draft of the ESMC.19

A Light Cleaning on the Outside, Still CRT on the Inside

The radical Marxist authors of the first draft of the ESMC associated with Unión del Barrio were removed from the Ethnic Studies curriculum committee after the SBE rejected it in August of 2019. Angered that their first draft had been rejected, the fired authors and supporters of the original ESMC first draft formed the “Save CA Ethnic Studies” coalition in 2019, and then the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium (LESMCC) in 2020 to push their original vision of the ESMC on K-12 public school districts in California, and have since become active in pushing liberated Ethnic Studies bills in 19 other states.20

Meanwhile the remaining authors of the ESMC addressed the biggest complaints about the first draft and removed much of its anti-semitic language, although its guiding principles remained intact. And though the ESMC retained its focus on the history, heritage and struggles of four core racial groups — African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, and Native-Americans — it added lessons on other minority groups like Sikhs, Armenians, Koreans, and Filipinos. Of greater concern, the subsequent drafts of the ESMC kept CRT as the “key theoretical framework and pedagogy” of Ethnic Studies. Manuel Rustin, a Pasadena Unified School District history teacher and chair of the IQC’s subcommittee that wrote the ESMC first draft, defended keeping CRT as the backbone of Ethnic Studies in general, and the ESMC in particular:

“Ethnic studies without Critical Race Theory is not ethnic studies. It would be like a science class without the scientific method then. There is no critical analysis of systems of power and experiences of these marginalized groups without critical race theory.”21

Thus it comes as no surprise that CRT found its way into the LCHS Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee when LCHS Principal Cartnal distributed select chapters of the ESMC to attendees at its first meeting in Fall of 2022. As mentioned previously, Cartnal passed along the ESMC’s guiding principles and the teachers discussed the first chapter. He also distributed a sample Ethnic Studies-infused English Language Arts course outline from Pajaro Valley Joint Unified School District (PVJUSD) in Watsonville, CA. The Pajaro Valley USD Ethnic Studies course was developed in 2019 and approved by its school board in 2020. The course clearly takes a liberated approach to the teaching of Ethnic Studies and embodies the ESMC’s chapter 1 foundational value of raising a critical consciousness in students.22

Quoting from the Pajaro Valley English course description Cartnal distributed to LCHS Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee members at its first meeting:

“…This course aims to educate students to be politically, socially, and economically conscious about their personal connections to local and global histories. By studying the histories of race, ethnicity, nationality, and culture, students will develop respect and empathy for individuals and groups of people locally, nationally, and globally to build self-awareness, empathy and foster active social engagement.”23

Note the focus on identity and exhortation to foster “active social engagement” in students. Though it is not known to what extent the LCHS Ethnic Studies Teacher Committee realized the critical pedagogical orientation of the ESMC materials distributed by Cartnal, it is clear from Cartnal’s Board presentation on August 29, 2023 that the re-designed English 1 course incorporated the ESMC’s critical pedagogical approach:

How Will the English 1 Course Change?

At the August 29, 2023 LCUSD Governing Board meeting, LCHS Principal Cartnal presented a proposed English 1 modified course syllabus and an English 1 Ethnic Studies Reading List to the Board for consideration as attachments to the meeting agenda.24 The course description explicitly acknowledges the critical pedagogical approach to reading works added to the English 1 syllabus to meet the Ethnic Studies requirement:

“Welcome to 9th grade English! In freshman English, you will build on the knowledge and skills learned during middle school and study a wide range of diverse and complex literary genres (short stories, plays, poetry, novels, and non-fiction). As you close-read prominent works of literature through different critical lenses, this class will strengthen your literary analysis, argumentation, research, and writing skills.”

A critical lens refers to a specific theoretical framework or perspective that scholars and students use to interpret, analyze, and critique a text. Though there are multiple possible critical lenses that the English 1 teachers could use and neither the course syllabus nor Cartnal identified which critical lens would be used, it is reasonable to conclude that they will use the critical lenses used in the ESMC, which are CRT, Marxist criticism, Postcolonial criticism and Queer Theory.25

Similarly, the modified English 1 Reading List acknowledges its roots in the ESMC, “In adapting our units to meet the unique needs of ethnic studies, we have amended our focus to also meet the thematic elements of ethnic studies per the guidance offered in CDE’s Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum.”

And though Principal Cartnal did not explain to the Governing Board in his August 29th presentation which new works of literature would be substituted into the English 1 reading list to meet its Ethnic Studies goals, comparison of the new and past reading lists and syllabi, confirmed by Cartnal in my correspondence with him after the meeting, indicate the following literary works will be read when addressing the five minority ethnic groups Cartnal had earlier identified would be studied:

African American: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry and/or Just Mercy (YA edition) by Bryan Stevenson

Hispanic / Latino / Latina: The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

Asian-American Pacific Islander: The Paper Menagerie by Ken Liu and/or Crying in the H Mart by Michelle Zauner

Native American: The Man to Send Rain Clouds by Leslie Marmon Silko and/or Indian Education by Sherman Alexie

Armenian American: To be determined.

Works that used to be read in English 1 that will supposedly be displaced to English courses in later years to make room for the above works include Othello by Shakespeare, Antigone by Sophocles, and The Iliad by Homer.26

What’s the Risk of Turning English 1 into a Critical Pedagogy Class?

What was not revealed during Cartnal’s August 29, 2023 Board presentation or subsequent Q&A with Board members is the exact context in which the above listed Ethnic Studies literary works will be presented and discussed in the classroom. Presumably the works will be assigned reading to English 1 students, and it is safe to guess that classroom discussion will focus on “enriching students’ understanding of a variety of narratives while reinforcing foundational reading and writing skills needed in high school and beyond” through a “critical lens” as stated in the course syllabus. What remains unknown is how much background reading and discussion will be involved in framing that critical discussion and how much critical race theory will be used to develop students’ critical consciousness as the ESMC objectives state. As the LESMCC activists in their teacher training webinar admitted, they never explicitly teach CRT in their K-12 classrooms to their students or label CRT tenets as Critical Race Theory, but they use it as a theoretical framework in how they carry on classroom discussion with students and they infuse it into all of their lessons. Lupe Carrasco Cardona explicitly told teachers:

“In a K-12 education (environment) what we’ve seen in our work is that, except for now because it’s such a hot topic in education, K-12 teachers didn’t usually get up and say, ‘well today we are going to do a lesson on Critical Race Theory.’ What they did is they took those tenets of Critical Race Theory — the pedagogy or the methodology — and create pedagogical models, many that you are going to see today. They took ideas in Critical Race Theory and made it come alive in the classroom so that students could engage in an anti-racist project.”

It is also unknown how much time will be devoted in class to discussing the four themes disclosed in Cartnal’s presentation — identity, history and movement, systems of power, and social movements and equity. It is known that several English Language Arts courses at LCHS, not just English 1, began this school year with a lesson on identity and intersectionality, just as the ESMC prescribes. The concern of every parent should be the indoctrination of their children into the tenets of Critical Race Theory and the explicit admission of teachers like Cardona to “use Critical Race Theory connected to Ethnic Studies in a way to empower and to create social justice activists out of our students.” While some parents may agree with the aspiration to turn their kids into social justice activists, they should do so on their own outside of school. Most parents would prefer that the English 1 course focus on developing the skills as described in the LCHS Course Catalog:

“English 1 is a foundational year that is designed to provide students with the necessary skills for future success in English Language Arts. The course will provide a thorough foundation in annotation and literary analysis, as well as introduce students to argumentation, research, and rhetorical analysis. This course’s selections are genre-based, including short stories, novels, poetry, and drama. Students are expected to develop their analytical skills, differentiate between analysis and summary, participate in class discussions and group projects, and overall, to become more critical readers, effective speakers, and thoughtful writers.”

The ESMC clearly has its root in radical revolutionary ideology that its original authors fought fiercely to keep in. While overt anti-semitism and the most offensive language was scrubbed from the first draft of the ESMC, its CRT lens and critical pedagogical orientation remain. When LCUSD embarked on its Ethnic Studies course creation process two years ago, Cartnal looked to the ESMC for guidance and it is clear from the documents released thus far that the ESMC has made its way into the pilot English 1 course. The danger of critical pedagogy is that its self-stated purpose is to tear down established structures toward the goals of achieving equity and a new, liberated society. The pilot English 1 course risks creating an ideological training ground at the expense of developing for students a foundation in writing and literature. Classic works of literature that were formerly read in English 1 like The Iliad, Antigone and Othello have been removed to make way for lesser works that highlight the struggles of specific racial minorities. Parents should ask themselves if this is a worthwhile trade-off.

The current Ethnic Studies / English 1 implementation is merely a pilot at this point and Cartnal explained to the Governing Board at the August 29, 2023 meeting that course adjustments would be made based on student, teacher, and community feedback. Though Cartnal did not explain how parents could submit feedback when asked by Board member Octavia Thuss, parents always retain the right to contact Cartnal, district staff, and the Governing Board with their thoughts. The district does not have to meet the AB-101 mandate by incorporating a critical pedagogical oriented Ethnic Studies into its curriculum. In fact, by doing so it has violated its promise made in 2021 that CRT is not an adopted part of the district’s instructional curriculum. AB-101 does not require that the Ethnic Studies course be in place until the 2025-26 school year so there is ample time for the district to make course adjustments.

Critical pedagogy is the application of critical theory to the method and practice of education (i.e. pedagogy) and was founded by neo-Marxist Brazilian philsopher Paulo Freire in the late 1960s, though the term critical pedagogy itself is credited to his disciple Henry Giroux. Freire explained the theory in his landmark book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), which as James Lindsay notes in his Social Justice Encyclopedia is “presently considered something like foundational canon in nearly every school of education and pre-service teacher-education program in North America (and beyond.)” The goal of critical pedagogy is to help students achieve a critical consciousness, empowering them to recognize and challenge oppression in all its forms. Rooted in critical theory, it believes that education can be a tool for social change and emphasizes the importance of education being a dialogic process, where students and teachers learn collaboratively. Critical pedagogy traces its roots to Karl Marx and the post-modernists, and is foundational to critical race theory, as is well illustrated in this slide from a CRT educator’s professional development webinar on “CRT and Equity in the Classroom: An Introduction”:

California Assembly Bill 2016 (AB 2016), Chapter 327 of the Statutes of 2016, introduced by California Assemblyman Luis Alejo, added Section 51226.7 to the Education Code, which directed the CDE’s Instructional Quality Commission (IQC) to develop a model curriculum in Ethnic Studies, which is called the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum. The ESMC was adopted by the SBE on March 18, 2021 after a long and contentious development process that spanned four years, three drafts, and over 100,000 public comments. https://edsource.org/2021/a-final-vote-after-many-rewrites-for-californias-controversial-ethnic-studies-curriculum/651338

For the record, after initially suggesting that it was aiming to add a one-year dedicated Ethnic Studies course senior year, Cartnal and his teacher committee changed their mind to instead recommend option #4 — embed Ethnic Studies into an existing A-G Course, English 1 in this case, which is taught in 9th grade.

Christina Hale-Elliott, LCUSD DEI Recommendations for Sustainability: Final Report (August 2020) as presented to the LCUSD Governing Board at its meeting on August 11, 2020.

Official notes from the DEI Subcommittee for Curriculum and Development may be read here. Note that this subcommittee was part of the LCUSD DEI Special Committee which met from November 2020 until it was disbanded in August of 2021. The committee was different than LCUSD DEI Oversight Committee, which continues to meet as of the publication date of this article in its third year of existence.

This definition is taken from the California School Boards Association (CSBA) FAQ on Ethnic Studies from July 2021.

Wikipedia entry for Ethnic Studies (fetched Sep. 12, 2023.)

Definition from the Alliance for Constructive Ethnic Studies.

Arshad Imtiaz Ali, Education at War: The Fight for Students of Color in America’s Public Schools, Fordham University Perss, (2018.)

AB-101 explicitly states, “The bill would authorize, subject to the course offerings of a local educational agency, including a charter school, a pupil to satisfy the ethnic studies course requirement by completing either (A) a course based on the model curriculum in ethnic studies developed by the commission, (B) an existing ethnic studies course, (C) an ethnic studies course taught as part of a course that has been approved as meeting the A–G requirements of the University of California and the California State University, or (D) a locally developed ethnic studies course approved by the governing board of the school district or the governing body of the charter school.”

“Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Guidelines: Guidelines for the 2020 Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum” (last updated Nov. 03, 2022.)

“What is Union del Barrio?” on the Union del Barrio website.

“Union del Barrio Political Program: Congreso Nacional 12-2017: A Program for Political Direction, Consciousness Raising, and Liberation Struggle,” originally published in 1986 but revised multiple times since.

Ibid.

“2020 Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Advisory Committee Members Summary List,” California Department of Education.

For example, see “Editorial: California’s proposed new ethnic studies curriculum jargon-filled and all-too-PC,” Los Angeles Times, Aug. 04, 2019, Karin Klein, “Opinion: California fixed the anti-Semitism in it’s ethnic studies program, but what’s left is still a mess,” Los Angeles Times, Sep. 30, 2019,

Newsom said in response to questions from Jewish Journal at the time, “And let me also apologize on behalf of the state for the anxiety that this produced. It was offensive in so many ways, particularly to the Jewish community.” https://www.calethstudies.org/liberated-ethnic-studies-in-the-classroom

Sylvia Kwon, “Ethnic Studies Legislation: State Scan,” WestEd, February 2021. In addition, Minnesota recently passed a bill requiring the teaching of liberated Ethnic Studies in all K-12 classrooms. See Grace Deng, “Minnesota House committee passes ethnic studies requirement,” Minnesota Reformer, Feb. 28, 2023.

John Fensterwald, “A final vote, after many rewrites, for California's controversial ethnic studies curriculum,” EdSource, March 17, 2021.

Critical consciousness is a another term attributed to Paulo Freire, this one from the early 1970s, and “describes how oppressed or marginalized people learn to critically analyze their social conditions and act to change them.” [Source] A more thorough definition of critical consciousness is:

“Critical consciousness is, in short, having adopted a critical mindset, in the sense of critical theories. It is to have taken on a worldview that sees society in terms of systems of power, privilege, dominance, oppression, and marginalization, and that has taken up an intention to become an activist against these problematics. To have developed a critical consciousness is to have become aware, in light of this worldview, that you are either oppressed or an oppressor—or, at least, complicit in oppression as a result of your socialization into an oppressive system. To have a critical consciousness is to be aware of—and generally unhappy about—your positionality in society, i.e., your relationship to systemic and institutional power as determined by Theory and based mostly on facts concerning what demographic groups you are a part of.

Critical theories see the world as being constructed in terms of power dynamics that oppress certain people (minoritized groups) to the benefit of the dominant group(s). They advocate awareness of this purported fact (see also, consciousness raising and false consciousness) and radical activism to change it (see also, antiracism, for example). Gaining a critical consciousness means achieving this awareness, realizing this awareness must be spread to others, and understanding that radical or revolutionary activism is needed (usually urgently) to change the system to end its injustices.

…

When someone has adopted a ‘critical consciousness,’ they are likely to be hypersensitive to issues surrounding race, sex, gender, sexuality, ability status, weight, national origin, and economic class, and they are expected to share this awareness (consciousness raising), often by attempting to expose the ‘hidden biases,’ ‘unexamined assumptions,’ or ‘inherent contradictions’ in the system in order expose its injustices and thus lead to its deconstruction, dismantling, or subversion, i.e., a social revolution. This is most often done by problematizing things, which is to say finding issues (like potential offense or hidden racism—see also, code and mask) wherever they can be found. This mindset begins by rejecting questions like ‘did racism occur?’ and replacing them with ‘how has racism manifested in this situation?’”

Source: https://newdiscourses.com/tftw-critical-consciousness/

Page 430 of chapter 6 of the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum.

The English 1 course syllabus and reading list may be downloaded and viewed from LCUSD’s agenda website for the August 29, 2023 meeting.

In educational theory, the multiple possible critical lenses could include:

Feminist Criticism: Focuses on how literature represents gender roles, the status of women, and the power dynamics between genders. Feminist criticism seeks to identify and challenge patriarchal values in literature.

Critical Race Theory: The application of critical theory to the examination of racism and race relations in society, particularly systemic racism.

Marxist Criticism: Examines literature in the context of class struggle, socioeconomic conditions, and the effects of capitalism. It often looks at how characters and narratives are shaped by economic forces or how they reflect class dynamics.

Psychoanalytic Criticism: Draws on the theories of Sigmund Freud (and other psychoanalysts) to explore the unconscious desires, fears, and motivations of characters, or the psychological depths of the author.

Postcolonial Criticism: Examines literature from the perspective of formerly colonized societies and scrutinizes themes of identity, cultural conflict, and the consequences of imperialism and colonialism.

Queer Theory: Analyzes texts through the lens of sexuality, gender identity, and LGBTQ+ experiences. This approach challenges normative views on sexuality and gender.

New Historicism: Instead of seeing literature as timeless or autonomous, new historicism views a text as a product of its time, influenced by historical and cultural forces. Texts are examined alongside non-literary texts (e.g., historical documents) from the same period.

Deconstruction: Associated with the philosopher Jacques Derrida, this approach emphasizes the inherent instability of language and meaning. It often involves dissecting binary oppositions (like good/evil, male/female) in texts to show how these binaries are not fixed or stable.

Ecocriticism: Examines the relationship between literature and the natural environment, considering themes like ecology, human interaction with landscapes, and environmental justice.

The common thread among the above except 4, 7 & 8 is they are all branches of Marxism or neo-Marxism.

Personal correspondence with LCHS Principal Cartnal on September 11, 2023.

Thank you for this, I’m a 9th grader parent at LCHS. My jaw dropped after reading about the ethnic studies pilot. Especially bad is that major works of world culture, such as the Iliad and Othello were displaced by some modern day “writings”. I happen to have been born in the former USSR and had to endure years of Marxism studies at the university and post-grad level, so I know a bit more than most parents on this subject. Ironically, Marx himself was a pathological racist and there are many quotes from with his insane views on Africans (he used a slur), Slavs, Mexicans, Jews, etc. he called entire ethnic groups counter-revolutionary destined to perish. I would love to quote those at the next parent meeting. The intentional effort to sow ethnic loathing and hatred is unacceptable. I will contact the principal.